The Song of Bartleby: A retelling of Melville’s short classic

The Wonder Twins

The limerick is such a simple form of poetry. And yet its rigid structure makes it surprisingly difficult to write a good one. But what’s even more challenging is to trace the limerick back to its ancestral origins. Did the Irish really invent the limerick? And what was the very first limerick?

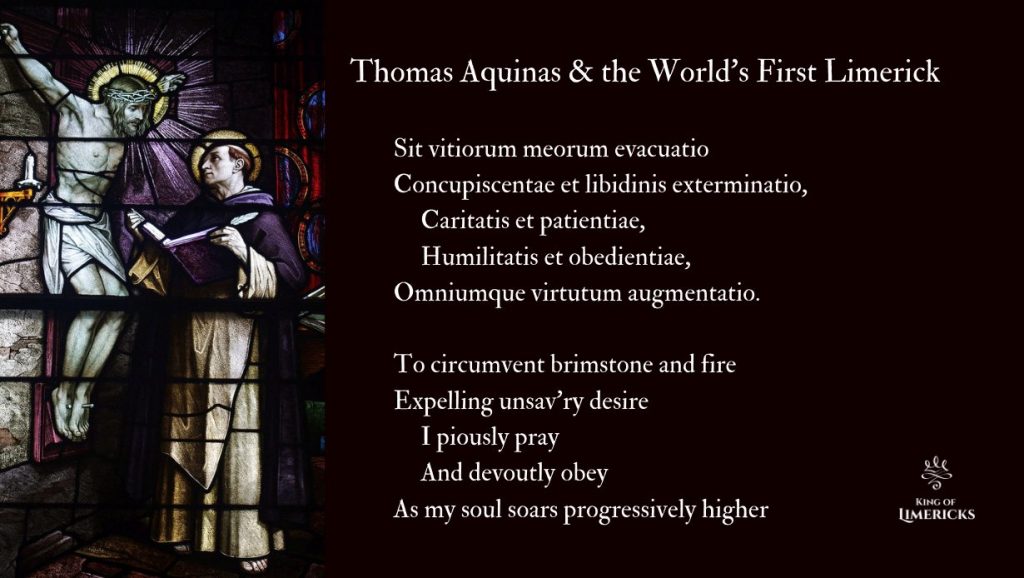

It’s hard to say with absolute certainty, but we have evidence to suggest that Saint Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) wrote the first limerick sometime in the 13th century. His five-line rhyming verse, penned in medieval Latin, survives in the archives and appears to be the oldest example of this form. However, the meter and syllable count of this old poem don’t quite satisfy the modern definition of a limerick. And it much more closely resembles a prayer than a wisecrack. Still, it seems to be the oldest ancestor of what we now call the limerick.

So who was Thomas Aquinas, and why was he writing limericks? And, more importantly, how did the limerick get from the Dominican monastery to the bordello? In the following article, we’ll do our best to answer these and other puzzling questions.

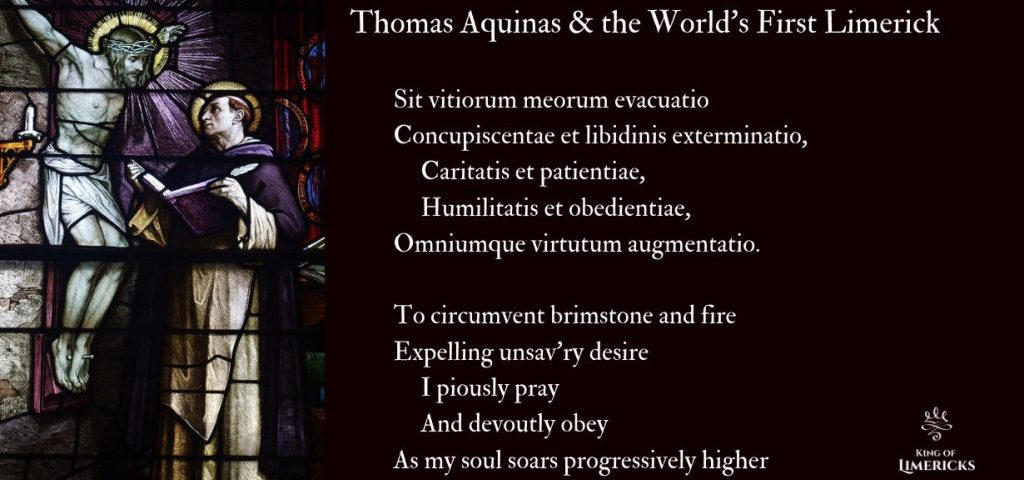

The very first limerick, by Thomas Aquinas

You won’t find it in a collection of the world’s most salacious limericks, but it appears in the Roman Catholic Breviary, a compilation of hymns and prayers. Here it is.

Thomas Aquinas, in original 13th century Latin

Sit vitiorum meorum evacuatio

Concupiscentae et libidinis exterminatio,

Caritatis et patientiae,

Humilitatis et obedientiae,

Omniumque virtutum augmentatio.

If you can imagine hearing this poetic morsel being read through clouds of incense, with shafts of light radiating through the stained glass windows, it’s probably quite moving. But for those of us less familiar with academic Latin, it doesn’t do a whole lot.

Thomas Aquinas, in plain English

To overcome the language barrier, we have a translation from Irene Blase, professor of ancient languages from the University of Chicago.

Verbatim translation by Irene Blase

Let it be for the elimination for my sins,

For the expulsion of desire and lust,

[And] for the increase of charity and patience,

Humility and obedience,

As well as all the virtues.

Well, now we get a much better idea of what Saint Thomas, the Angelic Doctor, was trying to say. Still though, it doesn’t sound quite like the limericks that we’re used to reading. She may have been an expert in Latin, but she was no master of anapest.

Thomas Aquinas, now that’s a limerick

Until now, those were the only two versions of the Aquinas limerick available. But this year, amidst volleys of coronavirus and conspiratorial speculation, I took it upon myself to make a real limerick out of it.

A bona fide limerick from Thomas Aquinas

To circumvent brimstone and fire

Expelling unsav’ry desire

I piously pray

And devoutly obey

As my soul soars progressively higher

You’ll notice the poem now has nine syllables in each of the two first lines, followed by five and six syllables in lines 3 and 4, closing with a 10 syllable denouement. This is in keeping with the traditional format. And moreover, the meter clearly consists of amphibrachs, providing the distinctively melodic rhythm.

Who was Thomas Aquinas?

For those unfamiliar with medieval church history, Thomas Aquinas was an Italian monk and one of the most important scholars in the history of the Catholic Church. His collected works, Summa Theologica, contain some extremely profound and influential commentary on theology and religious philosophy.

Many regard Aquinas as one of the 10 or 12 most important philosophers in the Western tradition. Perhaps he is best known for applying the rational philosophy of Aristotle to the tenets of Christianity.

Was it really the first limerick?

Before we can answer this question, maybe we need to define our terms. What do we mean by limerick, and what do we mean by first?

If a limerick is nothing more than a series of five lines with an A-A-B-B-A rhyme scheme, then yes, we have a limerick. But most poets expect a little more from a limerick. Traditionally, the syllable count by line is something like 9-9-6-6-9, with some room for leeway. I often add an extra foot (3 syllables) to lines 1, 2 and 5, just to prolong the pleasure. But this only works with strict adherence to the meter.

Paramount to the number of syllables, is the meter in which they flow, or the rhythm. Anapest or amphibrachs make the poem gallop: da-DAH-da da-DAH-da da-DAH-da. Without the characteristic meter, you just have a handful of sentences that happen to rhyme.

Now rhyming poetry dates back at least as far as Homer and the ancient Greeks, around the 7th or 8th century B.C.E. But oral traditions that employ rhyming probably go back as far as the stone age. It’s hard to imagine that no one before the 13th century had tried rhyming in A-A-B-B-A, but written records are scant. Apparently, Aquinas’ pious poem provides the oldest known example in writing.

Evolution of limericks: From pious to prurient

This limerick by Aquinas also deviates from tradition by addressing the highest matters of heaven rather than the lowest levels debauchery. We tend to think of the limerick as a witty form of poetry that’s almost always lewd and lascivious. But clearly that hasn’t always been the case.

It was Edward Lear who really made the limerick famous in the mid 19th century. His poems followed the rhyme and also stuck to the meter. But his limericks were anything but obscene. Lear’s Book of Nonsense was actually more like a collection of nursery rhymes for young children.

It wasn’t until the late 19th century, however, that dirty poems began flourishing in this five-line format. And that’s when they first took the name “limerick” and developed their association with Ireland. For the next hundred years or more, every dirty minded rhymer with a pencil was scribbling naughty limericks and making young ladies blush.

Back to the roots of the limerick

They say you can’t go home again, but at this point, I’m reminded of another powerful quote from the Dominican saint.

“Everything imperfect must proceed from something perfect: therefore the First Being must be most perfect.” (Of God and His Creatures, page 64)

It may require too great a leap of faith to believe that the limerick from Aquinas was not only the first, but also perfect. Still, I contend that there was something righteous about it, something more high-minded than a lass from Madras with a remarkable set of anatomical features.

Limericks have enjoyed their lecherous hour in the limelight, proving that sex sells. Sure enough. Maybe it was just the Irish trying to get the upper hand. I believe James Joyce once said, in reference to the British and the Irish, that “the winners write the history and the losers write the poetry.”

Joyce also spoke to the ambiguity of his landmark novel, Ulysses, saying that no one could tell if was a joke disguised as a religion, or a religion disguised as a joke. And that’s precisely where I’ve been heading with my esoteric limericks.

It’s possible to write limericks about mythology, theology and metaphysics, but it’s difficult to get away from the fact that a limerick has a humorous ring to it. Anyway, I’m convinced that a religion without a sense of humor is useless. Like a limerick, religion needs to hold paradoxes and contradictions in a way that allows us to laugh at them.

Perhaps if Thomas Aquinas had only displayed a greater sense of humor, he’d still be celebrated today, in more than just a handful of dusty hymnals. Nevertheless, we owe him our gratitude, not only for synthesizing Christianity and Aristotelianism, but also for having the courage to write a religious limerick, long before it was considered cool.

Further Reading

If you enjoyed the story Thomas Aquinas and the world’s oldest limerick, please consider sharing the post or subscribing to the blog. You might also want to check out some of these popular articles:

- 13 Educational Limericks

- 10 Honey-Tongued Limericks about Shakespeare

- The History of Limericks

- Simply Gothic: A lyrical retelling of Poe’s “Black Cat”

- Serious Limericks: There once was an unsmiling rhymer

4 Comments

The original Latin can be sung beautifully to the tune of “SHE’LL BE COMING ‘ROUND THE MOUNTAIN” — which works well for limericks generally. Try it!

Oh, I tried it, ahahaha. Thanks to the author of this blog post, I’ve been wondering about his poetry, though it’s probably very niche and preservation of works has always been a significant problem.

Destroy my faults, Sacred Torpedo

Crush greed and excessive libido

Patient love, be my way

As I humbly obey

In virtues, O Lord, please make me grow

Nice one!