12 of the best limericks that aren’t dirty

Illuminated Limericks: ebooks and anthologies

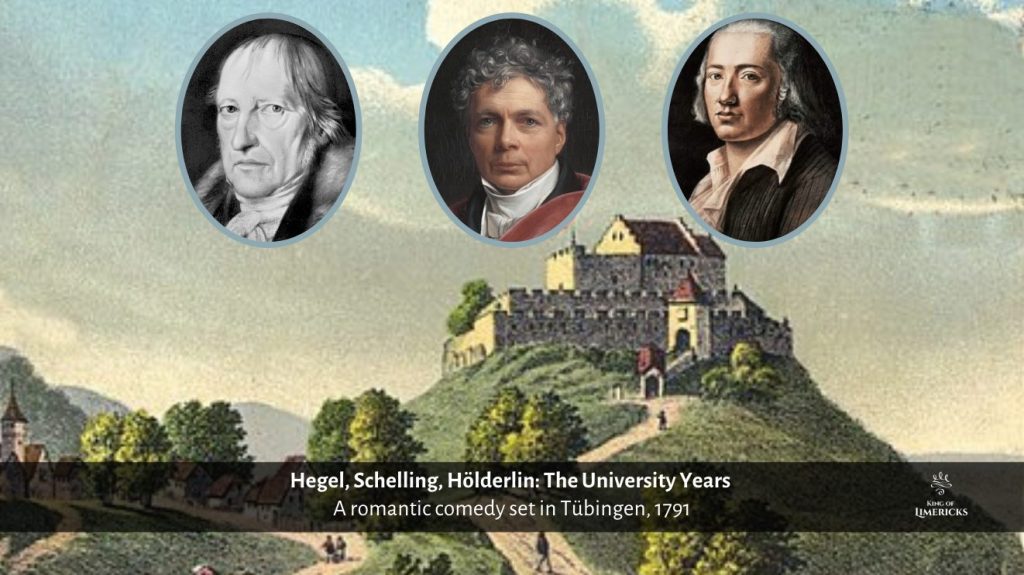

Between 1788 and 1793, G.F.W. Hegel attended the University of Tübingen, better known as the Tübingen Stift, a Protestant Lutheran Seminary in southern Germany. During these formative years, he was a roommate with the future poet Friedrich Hölderlin and the younger, soon-to-be philosopher Friedrich Schelling. The three became good friends and carried on many extraordinary conversations.

Friedrich Schelling entered the Stift in the autumn of 1790 at the precocious age of 15. The following drama takes place in the spring trimester of that school year. These were pivotal times in the arena in European philosophy. The French Revolution had just begun, and Louis XVI was still awaiting execution. Some historians mark 1790 as the end of the Age of Enlightenment. Descartes had made his point, and the ideas of Kant and Spinoza were just gaining currency. Clearly these young Hegelians were on the verge of something brand new.

Friedrich Hölderlin, plagued by mental illness, was destined to enjoy a short but stellar career as one of the finest poets of German Romanticism. No doubt the three roommates cast a profound influence on one another. And while the events of the following drama are entirely plausible, they are very unlikely to have unfolded in precisely this way. Instead, I have based the story on pure speculation with no substantiating evidence.

Dramatis Personae:

- G.F.W. “Wilhelm” Hegel, University student, age 20

- Friedrich “Frederick” Hölderlin, University student, age 21

- Friedrich “Freddy” Schelling, University student, age 16

- Heinrike Hölderlin, Hölderlin’s younger sister, age 18

- Louise Nast, Hölderlin’s ex-fiance, age 22

ACT I, SCENE 1

SETTING: Student apartment, Tübinger Stift, Tübingen, German Empire, Spring 1791

(HÖLDERLIN and SCHELLING seated in the kitchenette, drinking coffee, and arguing about Kant or Leibniz or something.)

HÖLDERLIN: Come on, Freddy, you can’t possibly be telling me that Kant’s antinomies are nothing but a tortured regurgitation of the Pre-Socratics. That every important metaphysical proposition was described better, and 2000 years earlier, by the ancient Parmenides. And that it would be obvious to all of us if only his collected writings hadn’t been lost or destroyed and reduced to a few meager fragments.

SCHELLING: Well yes, Frederick, that’s exactly what I’m telling you. Now, just listen for a—

(HEGEL enters, looking somewhat bleary, still in his nightgown.)

HÖLDERLIN: Gee-dubya! How nice of you to join us.

Everyone shakes hands, in accordance with German convention.

HEGEL: (half mumbling) Mm-hm. Can I just get a spot of coffee here, please?

HÖLDERLIN: You make out OK last night? When I left the cafe, you were enjoying an exclusive audience with quite a spellbound little Fräulein. I hope you were able to expose her to the naked truths about the Rights of Man, the Noble Savage, and all that egalitarian French passion of yours.

HEGEL: Well, I must say, it was rather late, wasn’t it.

HÖLDERLIN: Out with it, man. Did you get into her petticoats or not?

HEGEL: I’’m afraid I, um. Which Fräulein was that?

HÖLDERLIN: Oh, come on, Willie. You’re gonna make me say it in front of little Freddy here? Yeah, OK, I mean the skinny one with the big boobs.

HEGEL: Well, I’m afraid you’ll have to be a bit more specific than that.

HÖLDERLIN: Good lord! I guess you did make out alright then, didn’t you? You dirty old dog.

SCHELLING: It sounds like we have identified your type, eh Wilhelm?

HEGEL: I’m sorry to burst your precocious little bubble, young Freddy, but the simple coincidence that two women who happen to share a couple of inconsequential physical attributes also both happened to be in my company at various times over the course of the previous evening hardly constitutes what we could call a “pattern”.

HÖLDERLIN: “Inconsequential attributes”? Is that what the kids are calling them these days?

HEGEL: You seemed to be having quite a night yourself, Frederick. What were you toasting to this time? The latest edict from Robespierre? The fresh blossoms on the chestnut trees? You were drinking like a Hessian. I’m surprised you could see anything by the time you stumbled home.

HÖLDERLIN: And how on earth did you see me, with that ample bosom pressed right up to your face? Come on, now. We want details, don’t we Freddy?

SCHELLING: That we do. That we do.

HÖLDERLIN: Yes, sir. The girl was a knock-out, Freddy. Most becoming. We just don’t know how you do it, Wilhelm.

HEGEL: True enough. I wish I could let you in on the mystery. In fact, she was more than becoming. She was being and becoming.

SCHELLING: I just hope you weren’t coming and going—

HEGEL: She was a complete embodiment of the world soul. She was the French Revolution and the Royal Garden all in one. She was the. . . the unfolding of truth and reason . . . she was . . .

HÖLDERLIN: Incredible. Remarkable. Where’s she from anyway.

HEGEL: No idea really. She studies at the convent I suppose, with the Augustinians. Maria, or Mathilda. Something like that. Seems to have a thing for choir boys. I hummed a few bars of Telemann and she melted over my fingers like a fondue.

(A knock at the door)

MESSENGER: A message for you, Herr Hölderlin.

HÖLDERLIN: (opening the letter) Ah, wonderful—

HEGEL: What’s that, Frederick?

HÖLDERLIN: Oh, it’s just, nothing.

HEGEL: Ahh, I smell a woman. Does someone have a secret admirer?

(Holderlin shrugs off the remark and tucks the message away.)

SCHELLING: So, do you have plans to see this lady friend, Margarete, again?

HÖLDERLIN: Don’t count on it, Freddy. Surely you’re familiar with what’s called the “Platonic” relationship?

SCHELLING: Surely.

HÖLDERLIN: Yes, when a man gets stuck in the friend-zone, I mean really truly stuck beyond all hope, he is said to be in a “Platonic” relationship. Apparently, Plato was so notoriously incapable of sealing the deal, that the very condition itself was named after him. Now Wilhelm here, you see, he’s got some tremendous aspirations as a philosophy student. In order to surpass the greatest of greats, he aims to have the term “Hegelian friendship” enter the common vernacular, where a Hegelian relationship is just the precise opposite of a Platonic relationship.

(Turning to HEGEL) Have I got that just about right, Willie?

HEGEL: As you like, sir.

SCHELLING: Well, that’s certainly one way to make a name for yourself.

HÖLDERLIN: Eat your heart out, Don Giovanni.

HEGEL: Oh, Frederick here is just jealous. Ever since he broke off the engagement with Louise, he’s been having a helluva time. Poor tortured soul. She’s been trying to win him back ever since. And, of course, he misses that sweet honey pot. But he can’t stand the way she drones on endlessly about neo-classical tragedy, enlightenment dramaturgy, modern Romantic stagecraft, and all that crap. So he’s trapped between her soft flesh and her abrasive conversation. And there we have the world’s smallest and oldest love triangle. Q.E.D.

(A rap at the door)

MESSENGER 2: Master Hegel, there’s a visitor for you.

HEGEL: Did you catch her name?

MESSENGER 2: Fraid not, sir.

HEGEL: How’s she look? I mean—

MESSENGER 2: You’ll have to see for yourself.

HEGEL: Very well.

(Exit Hegel and Messenger)

HÖLDERLIN: This guy never quits. Anything goes with Herr Hegel, and everything flows.

SCHELLING: Heraclitus?

HÖLDERLIN: Naturally. Tell me, Freddy, can you keep a secret?

SCHELLING: But of course.

HÖLDERLIN: That message this morning was from my sister, Heinrike. She’s in Ludwigsburg at the moment, and she’d like to pay me a visit this weekend.

SCHELLING: Lovely.

HÖLDERLIN: Yes, indeed. My sister is a princess, a real angel. But you know Wilhelm. And well, I’d really prefer if he would, I mean, if I could—

SCHELLING: I’m quite sure that I see what you’re getting at.

HÖLDERLIN: Yes, I’d like him to keep his filthy hands off my sister. And it would be easier, better for everyone, if we could keep the two of them apart. Best then if he doesn’t know anything about her visit. I’m expecting her later this afternoon. I’d be much obliged if you could provide a little diversion.

SCHELLING: I’d be more than happy to, Frederick.

HÖLDERLIN: I promised to take her to the theater this evening. They’re performing one of her favorites from Lessing. But I’d forgotten entirely. I have to attend a seminar on the Eleusinian Mysteries.

(A knock at the door)

MESSENGER: Another message for you, Herr Hölderlin.

HÖLDERLIN: Oh, now what? (opening the letter) Hmm. Alright then.

(Exit Messenger. Enter Hegel, trying to read over Holderlin’s shoulder.)

HEGEL: What’s this now? Another secret lover? What is it about the melancholic that women find so irresistible?

SCHELLING: As a matter of fact, the female temperament is very commonly predisposed toward—

HÖLDERLIN: (interrupting) And what is it about lechery that brings all the floozies out of the woodwork?

HEGEL: Funny you should say that; I just had one hell of a time driving away this little wench downstairs. It seems—

HÖLDERLIN: Please, Wilhelm, spare us the sordid details of your wanton womanizing. (gesturing to Schelling) Remember the boy, after all.

HEGEL: So, what of it then?

HÖLDERLIN: Well, yes. It seems that Louise is going to be paying us a visit.

HEGEL: Oh, speak of the devil, the nettlesome miss Nast. How is that little beast of a woman these days? Nasty as ever, I’m sure! And still utterly heartbroken at your spurning? I knew she wouldn’t let you go that easily. She’s tasted the melancholy manna from heaven. Oh, poor Louise. She’s got it bad, hasn’t she?

HÖLDERLIN: Enough already.

HEGEL: You haven’t met Louise, have you Freddy? The Nast from the past! She could bore the lederhosen off of Mephistopheles that one could. Relentless. Incorrigible. Have you heard her thoughts on Schiller’s notion of the Beautiful Soul? Anything but beautiful. What this girl doesn’t know about beauty could fill the Library of Alexandria. Heavens to Hildegard!

HÖLDERLIN: Very well, I believe you’ve made your point.

HEGEL: As a matter of fact, our roommate appears to be taking great interest. Look at that twinkle in his eye. Freddy here has a soft spot for the damaged goods. Isn’t that right? Classic case of the Savior Complex, that’s what you have. Better keep these two apart. He’s much too young to be irreversibly corrupted by such a hopeless case as hers. Or? Hang on. Perhaps this could be the critical first step in your virile education, Freddy.

(pulling Holderlin aside)

Listen, I think I’m really onto something here. Here’s what we’ll do. When Louise arrives, I’ll tell her you’re at the library or the infirmary or whatever you like.

HÖLDERLIN: C’mon, don’t be ridiculous.

HEGEL: Hold on. Who’s being ridiculous? I know you can’t stand her. If we don’t take some initiative here, she’s going to show up and you’re going to find your own finite sovereignty the victim of her soul-crushing negation. That’s if you’re lucky! She’s ready to sink her nails in deep. I know you, Frederick. You’re too weak. Too fragile. You’re a slave in search of a master. And she’s a barnacle in search of a flailing vessel to latch onto and capsize. You lack the vigor to preserve your principal essence of being.

HÖLDERLIN: (putting up a weak resistance) Wilhelm, please, it’s not like that at all. She’s moved on…

HEGEL: (now taking Schelling to one side) Listen, Freddy. You’re free tonight, right? I don’t mean free in the absolute sense, that goes without saying, but I mean the specific personal sense. Well, of course you are. And our good friend here needs some help. So we’re going to run a little interference. And who knows, maybe you’ll get lucky. So here’s what we’re going to do…

ACT I, SCENE 2

SETTING: Shortly after lunch, the following afternoon, in the apartment

HEGEL: Now, Frederick, if you want this plan to work, you need to be well away from the apartment. Hiding yourself in the armoire just won’t do. You know how nosey little Louise is.

HÖLDERLIN: No, you’re right, of course. I’ll just hop down to the bakery for some kaiser rolls and then I’ll while away the time feeding the ducks by the pond.

HEGEL: Excellent. I’ll just give Freddy a thrashing over the chessboard here. And when Louise shows up, Freddy will kindly do away with her.

HÖLDERLIN: Very well. I’ll be back by 3 p.m. at the latest. I’d hate to miss, uh, afternoon tea.

(HÖLDERLIN exits while HEGEL and SCHELLING start a game of chess.)

HEGEL: You see, my friend, everything is going exactly according to plan. It’s as if events were unfolding in a predestined fashion, towards an ineluctable conclusion in which you and the scorned lover accompany one another to the theater and afterwards fulfill all of your most passionate fantasies.

SCHELLING: I’m not so sure about that.

HEGEL: No, no. It’s absolutely certain. Here’s a pair of theater tickets for you and the lady friend. Louise is crazy about Lessing, and tonight they’re performing “Nathan the Wise”. You can’t go wrong.

SCHELLING: Yes, I understand that much. I’m just not so sure if she’ll be so willing to accept the replica in place of the genuine article.

HEGEL: Nonsense. To any who have ears to listen, she will speak and speak and speak. Now, are you familiar with the Pomeranian opening? It’s all they’re talking about in the salons of Stuttgart these days. But allow me to show you how easily it can be thwarted.

(The pair spend an hour or so at the chessboard. Then comes a knock at the door.)

HEGEL: Aha! This must be her, Lothario. Fire up the charm and prepare to be stupefied.

(HEGEL opens the door, LOUISE enters boldly, and HEGEL greets her with affectation.)

HEGEL: Oh, Louise, what a delightful surprise.

LOUISE: Good afternoon, Wilhelm. Never mind the formalities. Where’s my Frederick? I’ve just been on a miserable carriage ride through the rain and mud. It must have been my driver’s first trip to the country. What an ordeal. But I know Frederick must be dying to see me.

(Hegel and Schelling exchange a knowing glance.)

SCHELLING: You must be Fraülein Nast. Enchanted to meet you. I’m Frederick’s roommate, Friedrich. But you can call me Freddy. He actually had to finish up some work at the library, but he suggested I keep you company. There’s a lovely pastry shop just up the street, if you’d care to join me.

LOUISE: You mean he’s not here? What kind of discourtesy is this? I didn’t travel all this way to be left in the hands of some adolescent errand boy.

SCHELLING: I beg your pardon, Miss Louise, but I’m sure he’ll be back just as soon as he can. And I think you’ll find the Zwetschgenkuchen most agreeable. They say it’s the crispiest in all of Baden-Württemberg.

LOUISE: Oh, really? Well then, what are we waiting for? I’m absolutely ravenous. And I do hope they know how to prepare a decent cup of coffee. These provincial baristas can be so inept.

(The conversation drifts off as SCHELLING and LOUISE exit the apartment. More time passes, and HÖLDERLIN returns.)

HEGEL: Hi there, Frederick. I wasn’t expecting you back so soon.

HÖLDERLIN: I’ve been tossing bread crumbs to the ducklings for over an hour. Surely they must have come and gone, no?

HEGEL: Oh, no. As a matter of fact, your Louise must have gotten delayed. Freddy just ran out for a loaf of pumpernickel. He should be back any minute.

(A knock at the door.)

MESSENGER: Afternoon, sir. There’s a woman outside to see Herr Hölderlin.

HEGEL: Sorry, but Frederick’s out at the moment. Tell her I’ll be right there.

Frederick, it must be Louise. You’d better hide yourself in the bedroom, just in case. And stay clear of the windows. I’ll run down to intercept your ladylove, and you won’t have to worry about a thing.

(HEGEL hurries downstairs to find Hölderlin’s sister, HEINRIKE, looking most delectable. He presents her with two tickets to the theater, and the two amble off, arm in arm.)

ACT II, SCENE 1

SETTING: That evening, at the theater

(The curtain falls midway through “Nathan the Wise” and the audience disperses for intermission. SCHELLING & LOUISE enter the lobby, engaged in a lively conversation.)

LOUISE: Oh, Freddy, please. Stop being so naive. What difference does it really make whether the sons receive the genuine heirloom ring from their father or simply one of his imitation replicas?

SCHELLING: Perhaps none, if you’re thinking only of this mundane material world. But if you allow for the existence of an eternal soul, then possessing the true ring, by which I mean the father’s genuine blessing, it makes all the difference in the world.

LOUISE: It’s always so simple with you boys and your seminary schooling, isn’t it? Either I accept the immateriality, indivisibility and immortality of the soul, along with the pervading immanence of the Almighty Father, or else I’m in league with the Prince of Darkness?

SCHELLING: Please, Louise, keep your voice down. You realize they still burn witches in these far corners of the kingdom?

(HEGEL & HEINRIKE enter, conversing with lukewarm enthusiasm.)

LOUISE: Well, speak of the devil. If it isn’t your wand-wielding roommate? And what’s Frederick’s little sister doing at his side?

HEGEL: Louise, Freddy, what a pleasant surprise. How are you enjoying this evening’s performance? I was just explaining to young Heinrike here the metaphysical implications of the

three rings and what it all means for the exclusivity of God’s chosen people.

HEINRIKE: Yes (rolling her eyes), his observations have been most illuminating. (Turning to Schelling) I don’t believe we’ve met.

HEGEL: Why this is our newest roommate, Mr. Schelling. Hasn’t your brother mentioned him? At a tender 15 years, he’s the youngest student at the university. Freddy, this is Frederick’s sister, Heinrike, visiting for the weekend.

SCHELLING: Sixteen, actually.

HEGEL: Excuse me?

SCHELLING: I turned 16 in January.

HEINRIKE: Oh, a Capricorn!

SCHELLING: Beg pardon?

HEINRIKE: Your zodiac sign. What day in January is your birthday?

SCHELLING: The 27th.

HEINRIKE: Oh, an Aquarius then. I see. How idiosyncratic! I’m a Leo myself. August 15th. Which is why the men can’t take their eyes off of me. No offense, Louise. Where is that heart-breaking brother of mine anyway? Didn’t he want to come to the play with you tonight?

LOUISE: No offense taken—

SCHELLING: As a matter of fact, Louise and I were just discussing the ring parable and what it means for the question of the soul.

LOUISE: Yes, Freddy here seems attached to the Sunday school notion of an eternal soul.

HEGEL: I’m afraid the lad has a rather one-dimensional affinity for the old Platonic paradigm.

HEINRIKE: It’s obvious to me that all three rings are replicas of equal value. Their authenticity is not the point. What matters is how the three sons choose to receive them, and in turn, how they go about living their lives in their father’s memory.

(SCHELLING looks to HEINRIKE and slowly nods with approval.)

HEGEL: Well, I’m also afraid that the feminine intellect is far too soft for these rarefied matters. And that’s why they have no place in the university. If they had their way, it would quickly become a breeding ground for irreligious extremism.

LOUISE: Why does everything always turn into a breeding ground with you, Wilhelm?

(HEGEL and LOUISE begin to joust.)

SCHELLING: I’m quite sure that was the interpretation that Lessing had in mind, actually.

HEINRIKE: Yes, I have no doubt that an Aquarius would understand these things. But it goes well beyond that. I mean, if the sons accept their father’s rings as real and genuine, then that perception of authenticity supersedes all else. There’s a psychological reality that cannot be argued out of existence. What we’re really talking about is polytheism.

SCHELLING: I concede that you’re absolutely right, Heinrike. And it’s funny you should bring up Hellenism, because I keep thinking about another allegorical ring, the Ring of Polycrates, from Herodotus. Are you familiar with that story?

HEINRIKE: Oh, of course. My brother and I read all the Greek histories as children. It’s a story about the Wheel of Fortune, is it not? Everyone’s luck is bound to change at some point, for better or for worse. That’s why the Pharaoh refuses to accept the alliance with King Polycrates, who seems to have an endless streak of good fortune. But it’s only a matter of time.

SCHELLING: Yes, that’s the standard reading. But what I see, it’s more about the necessity of loss and the price we all must pay for spiritual growth. The King has never lost anything he truly valued, and that’s why the Pharaoh can’t trust him. Until we’ve suffered some serious loss or given up something dear, we can’t really approach the Great Void. Of course, Christ is the ultimate embodiment of that notion. But what a treat to come across this idea in such an ancient text, prior even to the time of Socrates.

HEINRIKE: Intriguing observation, Freddy. Now speaking of fortune—can I ask you a personal question? I mean, when’s the last time you got lucky?

SCHELLING: In fact, I consider myself quite blessed to be living in this age of the Enlightenment, and to be attending this prestigious university, and to have two such admirable roommates as Wilhelm and Frederick.

HEINRIKE: How charming. It’s so nice to meet a man who can recognize his own good fortune. I’m beginning to feel somewhat fortuitous myself. Freddy, why don’t we skip the last two acts and go find someplace more quiet where we can talk?

(SCHELLING and HEINRIKE surreptitiously exit the theater together.)

HEGEL: But surely you can’t deny the rational, teleological procession of civilization and our species? And from there, you have no choice but to acknowledge the guidance of some higher intelligence, be it personal or impersonal. Which all points to the inexorable existence of an immaterial soul, suffused with that same irreproachable spirit. And being immaterial, it must also be indivisible and immortal. This is all so elementary.

LOUISE: Oh, Wilhelm. This whole line of reasoning is based on nothing but sophomoric assumptions. Like you’ve been reading too much Leibniz. Let’s accept for the moment that the universe is made up of a single divine substance. In this Oneness we all participate.

HEGEL: Precisely!

LOUISE: And yet our own individual existence, as discrete beings, proves that this substance is in some way divisible. And though it may be essentially immortal, who’s to say it can’t be divided or broken down into even smaller units, or Stückchen? The Stückchen may go on and survive beyond the death of our physical bodies, but why must you insist on some one-to-one correlation. If the soul is released, why not release into countless, innumerable particles? Seems to me that this would go a long way in explaining the inner tension and self-contradiction we all experience, the multiple souls that live in each breast, and Goethe would put it.

HEGEL: But that’s polytheism. Crude, pagan, and primitive.

LOUISE: Yes, I should have expected this sort of childish reaction from you. I never should have mentioned the multiple souls and multiple breasts. Why don’t we step outside for some fresh air?

HEGEL: Yes, I couldn’t agree with you more. Sometimes Lessing is too much, after all. Let’s get a drink then, shall we?

TO BE CONTINUED . . . (Subsequent scenes will be available shortly.)

Further Reading

If you enjoyed this entertaining excursion into the embryo of German Idealism, please consider purchasing one of my books or subscribing to the blog. You might also want to check out some of these popular articles.

- Limericks about German Philosophy

- Limericks about Dostoyevsky

- Limericks about Mental Health

- Limericks about Depth Psychology

- Simply Gothic: A lyrical retelling of Poe’s Black Cat