Unforgettable Limericks about History

Repentant Limericks about Guilt and Redemption

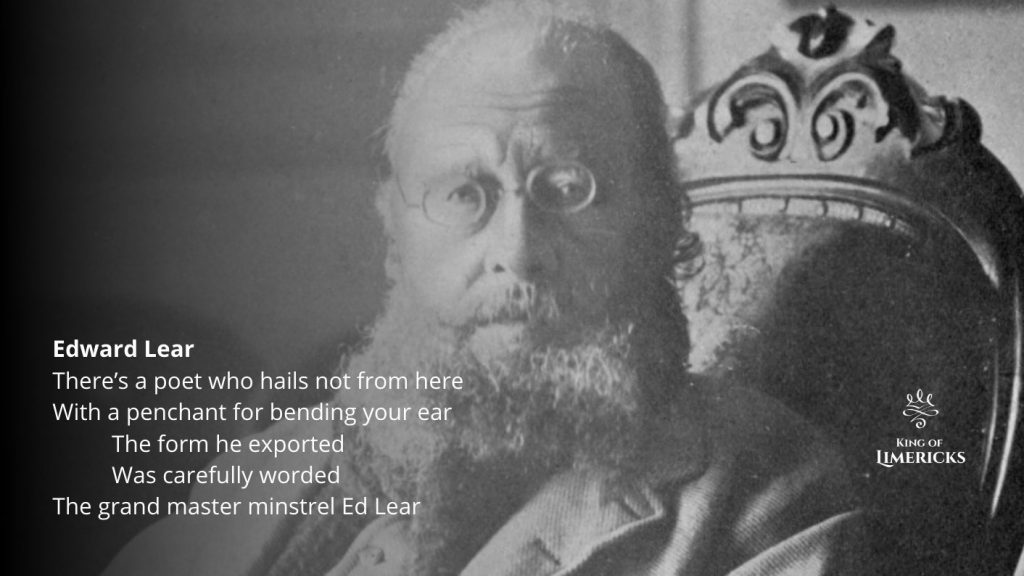

I only got into limericks about 15 or 20 years ago. I suppose it’s a long time to spend writing limericks. But at the same time, when you look back at the history of the limerick, a couple decades really doesn’t amount to much time at all. And sometimes I do look back to the beginning, and I wonder, whose idea was this anyway? Edward Lear often takes credit for inventing the limerick, but is that a true story or just a legend? Did Edward Lear really invent the five-line poem known as the limerick?

Edward Lear popularized the limerick with his many contributions to the genre, but he was not the inventor of this beloved form of poetry. Lear was a 19th century poet, artist and musician from Middlesex, England, and the author of numerous children’s stories and a volume of limericks entitled A Book of Nonsense. This collection brought widespread attention to the humorous type of poem known as the limerick. But these were not the first limericks ever written.

NOTE: This article contains a handful of limericks written by Edward Lear, which are in the public domain and free to share. It also includes four original limericks composed by me, about Shakespeare and Edward Lear, which may be re-used only with written permission.

Who was Edward Lear?

Edward Lear was born in Middlesex, England, in 1812, and produced a great legacy of work in various fields of art. As a young man in his late teens, Lear was already earning a living with his paintings and illustrations. And soon he became an expert draughtsman of ornithological and botanical drawings. As a musician, Lear composed a series of settings for the poetry of Alfred, Lord Tennyson.

But today Edward Lear is best remembered for his children’s stories, and best of all perhaps for The Book of Nonsense, a collection of humorous, family-friendly limericks published in 1846.

Edward Lear

There’s a poet who hails not from here

With a penchant for bending your ear

The form he exported

Was carefully worded

The grand master minstrel Ed Lear

The Book of Nonsense was not the world’s first introduction to the five-line rhyming poem known as the limerick, but it surely did a great deal to popularize the form. Lear published another collection of nonsense songs and poetry in 1872, bringing his total number of limericks to 212.

Examples of limericks by Edward Lear

As a writer of modern and strictly formatted limericks, sticking religiously to the rhyme scheme and anapestic meter, I have to say that the limericks of Edward Lear are something of a disappointment. Unlike the most enjoyable limericks, Lear never really pulls off a great double entendre and seldom reveals a surprise ending. But they do tend to paint an amusing scenario. Of course, he only labeled them as “nonsense”, so I have to give him credit for truth in advertising. He really did excel at nonsense.

My greatest objection to Lear’s limericks, however, are what I call the lazy rhymes, in which two different lines simply end with the same word. Technically, a word does rhyme with itself, but I find this device to be less than satisfying.

Consider the following examples, in what are considered to be some of his best and most popular limericks. (Note: You’ll see that Lear did not employ the same formatting typically used with limericks today. That development only came later.)

There was an Old Man with a beard,

Who said, “It is just as I feared!—

Two Owls and a Hen, four Larks and a Wren,

Have all built their nests in my beard.

There was an old man on the Border,

Who lived in the utmost disorder;

He danced with the cat, and made tea in his hat,

Which vexed all the folks on the Border.

There was an old person of Nice,

Whose associates were usually Geese.

They walked out together, in all sorts of weather.

That affable person of Nice!

We should keep in mind, after all, that Lear primarily intended his poems for children. And as such, he often manages to recount a a pretty fun story, as in the case of this one:

There was a young lady of Niger

who smiled as she rode on a tiger;

They returned from the ride

with the lady inside,

and the smile on the face of the tiger.

My response to Lear’s limericks

As limerick writers, we all owe a great debt to Mr. Lear for what he did with the genre. At the same time, I am a man of words, and I have a hard time holding my tongue when something doesn’t sit well. So with all due respect:

Dear Lear

Your limericks they could have been better

But your name it will live on forever

I just can’t get past

How with first line and last

You rhyme one and the same word together

But I also know that writing limericks can be a thankless profession. And it’s far easier to criticize a poet than to satisfy a reader. With that in mind, I say this:

Great Aspirations

Some limericks I think of as lazy

Repetitive rhyming betrays me

In dealing with verses

Who knows which is worse

Is there anyone willing to praise me?

If Lear did not invent the limerick, then who did?

It’s impossible to say who wrote the very first limerick, but the traditional form of poetry seems to have existed well before the 19th century. Kudos to Mr. Lear however, for raising it out of obscurity.

Although Edward Lear may rightly be considered the Father of Limericks, due to the popularity of his nonsensical anthologies, he is not actually the original inventor of the limerick. It should also be noted that Lear never used the word “limerick” to label what he called his “nonsense” poems.

Did Shakespeare write limericks?

There’s an erroneous rumor floating around the internet, and elsewhere, suggesting that William Shakespeare wrote, and maybe even invented limericks. Like many aspects of the Bard’s life and career, this too is a matter of some uncertainty. It probably depends on just how strictly you define a limerick.

Typically, Shakespeare wrote his plays and sonnets in flawless, iambic meter (da-DAH-da-DAH-da-DAH…), and almost never in the anapestic meter of limericks (da-da-DAH-da-da-DAH-da-da-DAH…). But there is this example of a drinking song from Othello (Act II, scene III). And this could very well be an early ancestor to the modern limerick.

And let me the canakin clink, clink;

And let me the canakin clink

A soldier’s a man;

A life’s but a span;

Why, then, let a soldier drink.

To be sure, the Bard has been the subject of many a limerick. In fact, they even hold contests for limericks about Shakespeare. But the prolific poet and playwright himself has left us with few, if any, limerical specimens of his own.

After writing a thousand or more limericks myself, including series about James Joyce, Dostoyevsky and Herman Melville, to name but a few, it’s odd that I should have overlooked old Bill. But you can be sure that I’ll get around to him soon enough. (See below.)

UPDATE: My series of limericks about Shakespeare are now complete and ready for viewing!

Do limericks come from Ireland?

The fact that this witty form of poetry bears the name of a city and county in Ireland leads many to assume that the poem itself originated in Ireland. But there’s no actual evidence to support this assumption. This remains a hotly debated topic in some poetry circles, however, as there’s really nothing certain to explain how the limerick got it’s name.

There are few competing theories, but the best explanation is that W. B. Yeats and other figures in the Irish Literary Revival belatedly applied the name limerick to this genre, some time after Lear’s death in 1888. By doing so, these Irish poets would create an implicit connection between this cheerful format and the Maigue Poets of Croom, in the County of Limerick.

This scholarly conspiracy theory makes sense considering the animosity between Ireland and England, particularly in those years of the Home Rule Movement leading up to Ireland’s independence. It could also explain how the limerick went from a form of poetry for children into a genre of smut and obscenity, as it turned from a proper English art form to a degenerate Irish endeavor.

The future of limericks

If limericks could go from G-rated and English to R-rated and Irish, who knows what the future could hold in store? I’ve spent the last two decades trying to bring limericks around to the next level of evolution, as a serious genre for philosophy and metaphysical speculation, while still retaining that special sense of levity. So I hope you’ll take some time to poke around my archives and see for yourself.

Bonus limerick about Shakespeare

While I was researching Shakespeare for this article, I came across a pretty interesting and often overlooked fact. In Romeo and Juliet, we all remember (Spoiler Alert!) that Juliet drinks a sleeping potion to make the townsfolk think that she has killed herself. Romeo was supposed to be in on the ploy, but he never got the memo.

And does anyone remember why the message never reached the young lover? Look again at Act V, scene II:

FRIAR LAURENCE

Who bare my letter, then, to Romeo?

FRIAR JOHN

I could not send it,–here it is again,–

Nor get a messenger to bring it thee,

So fearful were they of infection.

At that time, anyone would have known what was meant by the “fear of infection”. Juliet’s messengers were basically sheltering-in-place for fear of catching the plague. As it turns out, the quarantine can sometimes cost as many lives as it saves!

Romeo and Juliet

There’s a melodramatic persona

Who played tricks on the boys of Verona

But her message came late

And such was their fate

To be star-crossed by fears of corona

Further Reading

If you’ve enjoyed reading about Shakespeare, Edward Lear and the mysterious origins of limericks, please consider sharing the post or subscribing to the blog. You might also want to check out some of these popular articles:

- 14 of the Most Famous Limericks

- Limericks about Art History

- Limericks about the Bible

- Limericks about Dostoyevsky

- Serious Limericks: There once was an unsmiling rhymer

- What is a Limerick?