The Legend of Bell: Meta-myth of heroic discovery

History of Limericks: From Shakespeare to Spirit Rock

Since launching my website last year, I’ve already shared several hundred of my own original limericks covering topics as diverse as Moby Dick, metempsychosis and the DSM. But a lot of visitors have been coming here looking for examples of those well-known limericks of the lewd and tawdry variety.

The five-line limerick is a poetic form that dates back at least a couple centuries. Some say that the French troubadours started reciting limericks as far back as the Middle Ages. Edward Lear can really take credit for popularizing the genre in his Book of Nonsense, a children’s book published in 1846. But it wasn’t until the late 1800s that limericks gained their current name and developed their notoriously saucy reputation.

The most famous limericks revolve around matters of sexual innuendo and downright indecency. The best of them employ clever wordplay and surprising twists, although we almost always know what direction they’re heading in. The following collection contains all of the above, so stop right here if you’re easily offended by the graphic and off-color use of language.

Famous limericks (not for the faint of heart)

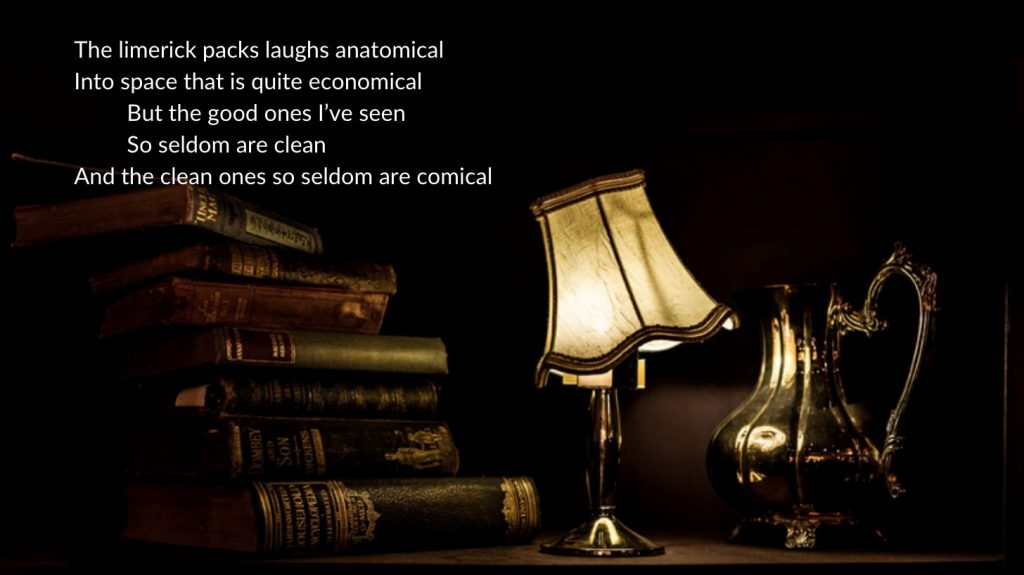

This well-known limerick, whose author remains unknown, curtly conveys the nature of the limerick, at least its prurient place in popular culture.

The limerick packs laughs anatomical

Into space that is quite economical.

But the good ones I’ve seen

So seldom are clean

And the clean ones so seldom are comical.

Indeed, the private parts do come up often in limericks. It’s a relatively low common denominator, but seldom fails to get a laugh. The next example, from Algernon Charles Swinburne, provides further evidence of that pattern.

There was a young girl of Aberystwyth

Who took grain to the mill to get grist with.

The miller’s son, Jack,

Laid her flat on her back,

And united the organs they pissed with.

And here’s another rhyme, equally indelicate, from the same author.

There was a young lady of Norway

Who hung by her toes in a doorway.

She said to her beau

‘Just look at me Joe,

I think I’ve discovered one more way.’

Livestock can provide another vibrant motif for the limerick, whether for the purpose of double entendre or towards the subject of bestiality.

An Argentine gaucho named Bruno

Said “Humping is one thing I do know.

A woman is fine,

and a sheep is divine:

but a llama is ‘numero uno'”.

There was a young lass of Madras

Who had a magnificent ass

Not rounded and pink

As you’d probably think

But was grey, had long ears, and ate grass.

And as we continue, we find that the themes of the most famous limericks do not vary all that much.

There was a young lady from Exeter,

So pretty that men craned their necks at her.

One was even so brave

As to take out and wave

The distinguishing mark of his sex at her.

While Titian was mixing rose madder

His model reclined on a ladder.

The position to Titian

Suggested coition,

So he ran up the ladder and had ’er.

Here’s another pair of provocative limericks which appeared in Season 1 Episode 1 of “The Crown“. Presumably they are traditional, of anonymous authorship.

There was a young lady named Sally,

Who enjoyed the occasional dally.

She sat on the lap

Of a well-endowed chap,

And cried “Sir! You’re right up my alley!”

There was an old Countess of Bray,

And you might think it odd when I say,

That despite her high station

Rank and education,

She always spelled “C*nt” with a K!

Seems that certain topics just never grow old. Here’s three more limericks of timeless endurance. I especially appreciate the elaborate internal rhyming in the first one.

I met a lewd nude in Bermuda

Who thought she was shrewd: I was shrewder;

She thought it quite crude

To be wooed in the nude;

I pursued her, subdued her, and screwed her.

There once was a young man named Cyril

Who was had in a wood by a squirrel,

And he liked it so good

That he stayed in the wood

Just as long as the squirrel stayed virile.

The thoughts of the rabbit on sex

Are seldom, if ever, complex;

For a rabbit in need

Is a rabbit indeed,

And does just as a person expects.

Shifting gears, ever so slightly (and no, that’s not some kind of sexual euphemism), I’d like to round out our list of 14 famous limericks with these two from Oliver Wendell Holmes, Senior and Norman Douglas, respectively. More up my literary alley, they deal with matters of theology and psychology.

God’s plan made a hopeful beginning.

But man spoiled his chances by sinning.

We trust that the story

Will end in God’s glory,

But at present the other side’s winning.

The frequenters of our picture palaces

Have no use for psychoanalysis;

And although Doctor Freud

Is distinctly annoyed

They cling to their long-standing fallacies.

More famous limericks worthy of mention

At the risk of disappointing my audience, but in hopes of not violating the laws of the internet, I have not included the famous limerick about the Man from Nantucket. There turn out to be multiple versions of this beloved limerick, all of them more or less equally obscene.

But there’s one more limerick I’m especially fond of, which is not obscene at all. I’m something of a man of words, but I also have a soft spot for numbers, so this one really pushes my buttons. It comes from British mathematician Leigh Mercer .

A dozen, a gross, and a score

Plus three times the square root of four

Divided by seven

Plus five times eleven

Is nine squared and not a bit more.

What makes a limerick a limerick

Obviously, the rhyme scheme of the limerick is imperative. But what I consider more important, and also more difficult to achieve, is the definitive anapest meter of the poem. The meter moves the words steadily forward, as the reader races towards the punchline.

Here’s an original limerick of mine for clarification.

A lim’rick’s not hard to define

But it needs to do more than just rhyme

It’s the meter that matters

The pitters and patters

If not you’re just wasting my time

But there’s something else that makes the limerick special, and it’s hard to put your finger on it. Something about the rhyme and meter of the poem makes it sound funny, even with the most solemn subject matter.

Then you have the brevity of the poem, which requires uncommonly efficient use of language on the part of the writer. And yet the five short lines always manage to convey a complete picture or story.

Lines one and two lay out the scene, but the secret sauce is somewhere in the middle. It’s lines three and four, even shorter and punchier, which add the vital element of suspense. A sense of anticipation primes the reader and sets up line five for a whopping dose of irony or an orgasmic release of tension — making it an ideal format for salacious wordplay.

The future of limericks

The recurring theme in the lion’s share of these limericks is easy enough to recognize. But we know from Edward Lear that the limerick was not always so naughty. And the limericks of Oliver Wendell Holmes and Leigh Mercer give me hope that limericks are already evolving towards a higher level of consciousness.

I’ve been pushing for that evolution for many years now, and my Tao of Fred anthologies offer hard evidence of those labors. So please check them out, if you enjoy thought-provoking limericks that combine economy of language with philosophical inquiry, as much as you enjoy the famous limericks about coition and exhibition.

Or, if you have a soft spot for naughty limericks and want to hear more of mine, which I seldom publish, feel free to contact me through the website to make a special request. You never know what I might come up with. I can assure you that other such readers have already been pushed well beyond the point of titillation.

Further Reading

If you enjoyed these famous limericks, please consider sharing the post or subscribing to the blog. You might also want to check out some of these popular articles:

- Honey-Tongued Limericks about Shakespeare

- Limericks about Dogma and Skepticism

- Limericks about Reference Books

- Limericks about Dostoyevsky

- Serious Limericks: There once was an unsmiling rhymer

1 Comment

She wasn’t what one would call pretty,

And other girls offered her pity.

So nobody guessed

That her Wasserman test

Involved half of the men in the city !

— anonomous

One of the greatest I’ve ever heard .