What is a Limerick and how do I write one?

Mindful Limericks about Buddha and Buddhism

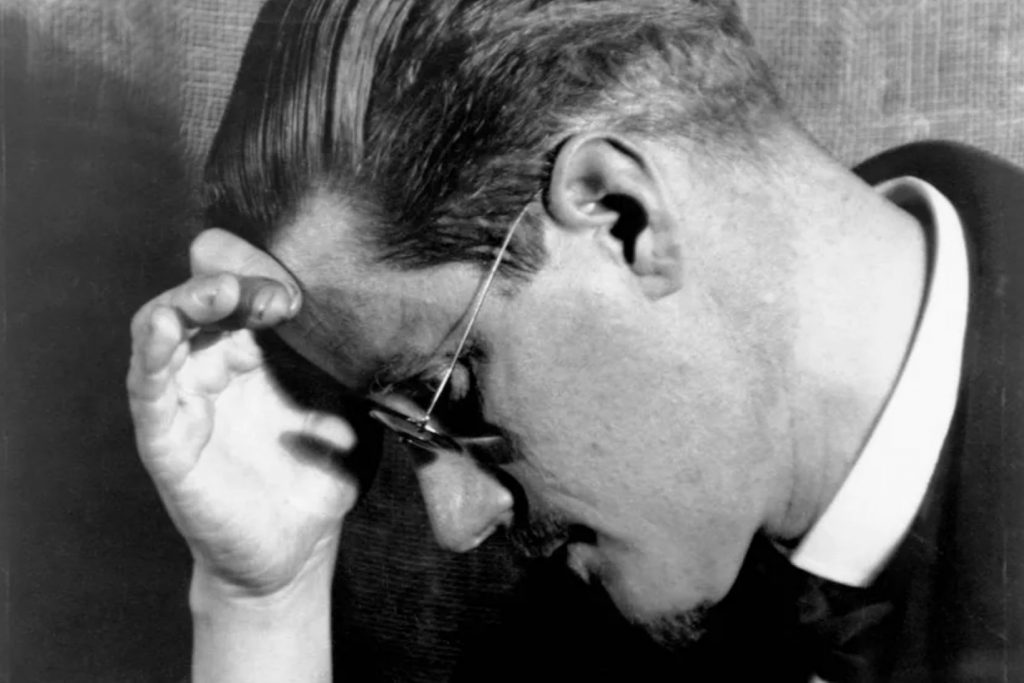

Part of what got me into writing limericks was reading James Joyce, and immersing myself for nearly a year in his masterpiece of high modernism, Ulysses. Many consider him the greatest novelist of the twentieth century, certainly the quintessential author of Ireland. And though it may be a misnomer, most of us associate the limerick with all things Irish.

Either way, Joyce had a knack for limericks, and I had a fascination with all things Joycean. At one time, you might have described my relationship with his opus as an obsession.

Re(ad)Joyce

Poetry students are said to be sissies

They wander through life like a string of ellipses

Other vocations

Achieve higher stations

But all of it’s useless unless it’s Ulysses

I spent a good many months tossing the vast and oftentimes impenetrable work about in my mind. Pulling it apart bit by bit, episode by episode, I slowly arrived at the realization that I could compose a concise synopsis, one that Joyce himself might even approve of, if he had an approving bone in his body.

My plan was to translate each of the novel’s 18 astonishing episodes into a quick and playful—yet also sharp and insightful—five line limerick.

About the novel, Ulysses

First a bit of background on this often-talked-about but less-often-read literary leviathan.

“Ulysses”

There once was an artist called Stephen

With Homer he tried to get even

So Bloom and he walk

Around Dublin and talk

And reflect upon what they believe in

Joyce based his self-consciously epic novel around the structure of Homer’s Odyssey. Ulysses contains 18 distinct episodes, each thematically corresponding to a specific episode of the Greek epic.

More than that, Joyce presents each episode in a unique narrative form and voice. And for the real geeks, there are elaborate charts to explain how each episode correlates to a certain part of the body, a specific color, and on and on. Scholars have also delighted over Joyce’s use of animal symbolism in the novel. The layers of this onion never seem to end.

And yet the setting is simple. And time in Ulysses is truly of another essence. The entire novel takes place on a single day, the 16th of June 1904, without a single character ever stepping foot outside of Dublin.

Ulysses retold with Limericks

Telemachus (episode 1)

It starts with a portion of prose

From “A Portrait” our character rose

A maker of mazes

His thoughts take us places

Like the Liffey his monologue flows

The novel’s protagonist, Stephen Daedalus , first appeared to readers in Joyce’s lighter novel, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. His name, Daedalus, comes from the master inventor of Greek myth, the one who built the labyrinth for the notorious Minotaur. The city of Dublin sits on the banks of the river Liffey.

Nestor (episode 2)

At school young Stephen is teaching

And into the past he is reaching

By his’try they’re bound

To a king and his crown

And a Pope who’s incessantly preaching

Part two finds us in history class, where Stephen mulls over the fact that he is tied to two masters. Ireland still belonged to Britain at that time, and unlike the British, the Irish were a devoutly Catholic race.

Proteus (episode 3)

Introducing the Protean mind

Streaming with thoughts of all kind

The king can change shapes

As our hero escapes

On a quest for a woman who’s kind

Episode three takes us on a long thoughtful walk with Stephen, whose mind wanders far beyond the streets of Dublin, into the realms of love and life and death.

Calypso (episode 4)

Calypso is leading a life of seduction

As Leopold seldom attempts reproduction

Their home goes to Blazes

While Bloom simply gazes

At maidens who gaily portend his destruction

Here we meet Stephens counterpart, a middle-aged, cuckolded, Jewish advertising salesman named Bloom. He has strong reason to suspect that his wife is having an affair with Blazes Boylan, and we have reason to believe that Bloom himself might also be unfaithful.

Lotus Eaters (episode 5)

Naughty Miss Martha she beckoned

For Henry was lonely she reckoned

But when she comes calling

He can’t help from falling

Some thirty-two Bloom feet per second

In part five, Bloom strolls about the city, running errands and ruminating over a cryptic love note in his pocket. As his mind wanders, it keeps circling back around various leitmotifs, including the acceleration of falling bodies.

Hades (episode 6)

In Hades his thoughts grow nightmarish

On the losses of loved ones we cherish

Of Rudy’s young face

And father’s disgrace

Each day umpteen thousand more perish

A trip to the cemetery for the funeral of a friend forces Bloom to think long and hard about mortality. He remembers his son Rudy who died much too young, and his father’s suicide, which brought a cloud of shame over the family.

Aeolus (episode 7)

There’s a paper where men shoot the breeze

Blowing steam over Mad Cow’s Disease

Home Rule is one topic

On which they’re myopic

For our heroes have both lost their keys

Part seven takes place at the newspaper office, and Aeolus is all about wind, which includes all manner of hot air and flatulence. The newspaper men argue over the hot topics of the day including Mad Cow’s Disease and Home Rule (Irish independence from Britain). While Stephen realizes that he left home without his house key, Bloom seems to have lost a customer by the name of Keyes.

Lestrygonians (episode 8)

There was an old Hebrew in search of a bite

In the lunchroom he witnessed a sickening sight

With the animals feeding

He felt like excreting

But a sandwich he managed to eat with delight

Meals are always something of a spectacle in the novel, as is most every bodily function you can imagine. Distracted by his own elaborate stream of consciousness, Bloom barely notices the ill-mannered chaos all around him.

Scylla & Charybdis (episode 9)

Now Stephen’s reasons seem so circumstantial

Prince Hamlet distracts him from problems financial

In a sharp dialectic

And a voice apoplectic

He maintains that the actors are all consubstantial

At the library Stephen argues with his classmates about art, economics, theology, and rather famously, “He proves by algebra that Hamlet’s grandson is Shakespeare’s grandfather and that he himself is the ghost of his own father.”

Wandering Rocks (episode 10)

Inverts and adverts and throwaway sheets

The minions meander through mazes and streets

A priest on parade

A state cavalcade

The double-edged spoon from which Ireland eats

Part ten leads us on a long and meandering walking tour of Dublin, and the novel begins to take a definite turn for the abstruse.

Sirens (episode 11)

A hero hears voices out over the oceans

While sirens fill glasses with succulent potions

His eardrum it pounds

With sonorous sounds

And somewhere a street girl seductively motions

In this episode devoted to music, we are reminded of Odysseus when he was tied to the mast trying to resist the call of those sinister seductresses.

Cyclops (episode 12)

I once knew a man who was prone to eruption

Lashing about at the eye of destruction

Exalting his land

Libation in hand

Then blinded by no man with no introduction

The mighty cyclops here takes the shape of narrow minded, outspoken, heavy drinking Irishman. Like the ancient Greek cyclops, this one is taken down by a man named no-man.

Nausicaa (episode 13)

O’er the sea sinks the sun with contrition

To be watching alone is the human condition

Like a rock on the sand

Honeymoon in the hand

Sowing seeds with no chance of fruition

In part 13, we are treated to one of the novel’s three incidents of masturbation, this time when Bloom covertly spies a good-looking girl on the beach.

Oxen of the Sun (episode 14)

There was a commotion in yon House of Horne

By three days of labor a mother was torn

While gentlemen waiting

Delivered words so degrading

The god-possibled soul of a new boy was born

This arduous case of childbirth brings us some of the most tortured prose in the whole mind-twisting novel. Thank goodness maternity wards aren’t what they used to be, but this might be part of why I wanted my kids to be born at home with a midwife.

Circe #1 (episode 15)

A vision at midnight by magic affected

But Bloom’s black potato is bound to correct it

Like a morsel of moly

To reverse the unholy

The remedy found where you least would expect it

Circe #2

Our pig-headed heroes wind up at Miss Bello’s

One of the district’s most fetching bordellos

Where spirits might render

Delusions of splendor

Finally conjoining these two wayward fellows

Circe #3

Stubbornly Stephen’s extending his nerve

“Non Serviam” he will duly observe

While Bloom takes a bow

Like a suckling sow

The artist announces that he will not serve

By far the longest episode in the novel, Circe brings our two heroes, Stephen and Bloom, together at a house of ill-repute after a long night of drinking. Homer’s Circe turned Odysseus men into swine, and these working girls conduct something of a black mass. After several hundred pages of thoughtful deliberation, Stephen Daedalus finally and definitively affirms his rejection of authority, of church, state and family.

Eumaeus (episode 16)

In the wee early hours their congress occurs

Perfectly sober Bloom sorely infers

That Stephen’s been euchered

Forsaken and suckered

And therefore he (Bloom) at this treason demurs

With a touch of compassion, Bloom leads the wounded Daedalus back to his home on Eccles Street, and tries nursing him back to life, or at least back to sobriety.

Ithaca (episode 17)

How shall this hero extinguish his passion?

With questions all posed in fastidious fashion

Then where does he head?

But straight for the bed

Right back to the womb and the voice of compassion

Narrated completely in Q & A format, this is the hero’s return to Ithaca, the coming home. He must ask himself if his wife has been faithful, if it matters either way, if life is worth living, and hundreds of other more or less mundane question.

Penelope (episode 18)

While fleshing things out at their Eccles address

Erupting with feelings she needs to express

She wonders half sleeping

Is Poldy worth keeping?

And answers in estrous emphatically Yes

Finally Leopold Bloom crawls back and into bed with his wife Molly. The question of fidelity remains, but the couple seems willing to move forward regardless. The novel concludes with a rapturous 40-page stream of consciousness by the female voice, ending at last with an explosive, life-affirming, and seemingly self-induced orgasm: “…yes I said yes I will Yes.” Talk about a happy ending.

Further Reading

If you liked these limericks about James Joyce, you’ll be sure to enjoy :

- Limericks about Shakespeare

- Limericks about Dostoyevsky

- Limericks about Moby Dick

- Limericks about Art History

- Limericks about German Philosophy

- Limericks about Me and My Limericks

- Edward Lear and the origin of Limericks

- What is a Limerick?