Clever Limericks about California

Paralogical Metaphors and Post-Rational Limericks

Since I launched the King of Limericks website and began sharing my poetic opus with the world at large, I’ve had the pleasure of connecting with writers and poetry lovers from around the world. Granted, limericks aren’t the first thing people start looking for when they log on to the Google. But after two years of persistent blogging, I’m fairly confident that when people do search for limericks, my website will come up pretty quick.

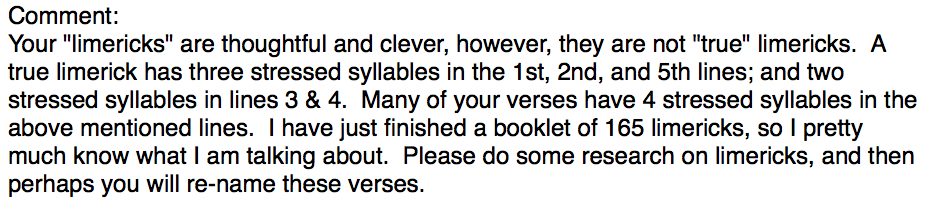

I don’t receive a ton of feedback on my limericks, but the majority of comments I get are pretty complimentary. This week, however, I received some highly unfavorable feedback from a very unhappy limerick critic. I have a habit of taking liberties with my limericks, extending the traditional form to include 11 or 12 syllables per line instead of the conventional 9. I call it poetic license, but the harshest critics seem to think that I’ve blasphemed the sacred art of limerick writing.

The Criticism

In the interest of full disclosure, I am sharing the original comment in its complete form. After leaving this comment on one of my blog posts, the same detractor proceeded to post similar remarks on two or three other articles. He also emailed me directly, in order to guarantee that I was aware of his impassioned plea that I do the research.

My assiduous reader, who shall remain anonymous, insists that I do some research on the “true limerick”. As a matter of fact, I have studied the genre quite extensively. From the proto-limericks of early English and the Middle Ages, to the watershed anthologies of Edward Lear, through the Irish appropriation and perversion of limericks at the end of the 19th century, I’ve done my homework. And what a colorful history it is!

Check out some of these articles to learn more:

- The History of Limericks from Shakespeare to Spirit Rock

- Thomas Aquinas and the Oldest Limericks

- Ireland, Limericks, and the Origin of the Specious

The Definition of a Limerick

When my critic draws a comparison between my limericks and the “true limericks”, it’s not perfectly clear which limericks he’s referring to. Supposedly, Edward Lear invented limericks back in the mid-1800s. Historians might quibble over the details, but he certainly popularized the form.

Lear’s five-line poems always used the AABBA rhyme scheme, but his meter was inconsistent, as were the number of syllables per line. And oftentimes, Lear would rhyme lines 1 and 5 by ending them both with the same word. Personally, I’ve always found that practice very annoying. (Although I’ve never felt the need to send any hate mail to air my grievances.)

When the Irish poets co-opted the form around the turn of the century, they named it the limerick, and added an unsavory element that many readers now consider an essential characteristic. For many, the limerick is simply a dirty joke that rhymes.

The meter matters

But the most important feature of the limerick, what makes it bounce, is its definitive meter. If you’re a poetry geek, you can call it anapest or amphibrachs. Basically, it’s one stressed syllable that is either followed by, preceded by, or sandwiched in between two unstressed syllables. So the end result goes something like this: da-da-DAH da-da-DAH da-da-DAH. It might also go da-DAH-da da-DAH-da da-DAH-da.

Each one of these tri-syllables is called a foot. Traditionally, most limericks have 3 feet (or 9 syllables) in lines 1, 2, and 5, and 2 feet (or 6 syllables) in lines 3 and 4. Once in a while there’s an extra syllable here or there, or a missing syllable. So in its purist purest form, the lines of a limerick would have 9, 9, 6, 6, and 9 syllables. But it could easily have 10, 9, 5, 6, and 9. So long as the meter or rhythm is maintained.

So my critic is on to something when he emphasizes the number of stressed syllables per line, rather than the total number of syllables, which can vary. That’s a great guideline actually. And his observation is correct. In many of my limericks, I stretch out lines 1, 2, and 5 to have 4 stressed syllables each. This allows me to cram a little more content into the verse, which is helpful when I write about German Philosophy, for example.

Responding to a Limerick Critic

According to this critic, who claims, in no uncertain terms, to “pretty much know what [he’s] talking about”, my poems are NOT limericks. By adding a few syllables to a few lines, I have apparently exceeded the bounds of the limerick. Or so he claims.

Well, this was my response. And you’ll notice it retains the purest limerick form, with a syllable count of 9-9-6-6-9.

There’s a critic who grumbles at lunch

With his knickers all up in a bunch

It’s a trifle you see

But we cannot agree

On the number of nanners per bunch

First of all, this guy is taking himself way too seriously. We’re talking about limericks for crackin’ out loud. As if they are merely “sparkling verses” if they don’t actually come from the Limerick County of Ireland. Now perhaps he doesn’t recognize the irony intended in the title, King of Limericks.

In that case, allow me to clarify once and for all, the name King of Limericks is meant to be a parody of false pride. Something like the Impresario of Pocket Lint.

In any case, his claim of some absolute standards concerning art and poetry is just absurd. I’m reminded of the critics who first reacted to the paintings of Monet and the Impressionists as sloppy “palette-scrapings on dirty canvas.” And then there were the music critics of the 1950s who announced that Elvis fans deserved “a solid slap across the mouth”, and the reviewers a decade later who understood the Rolling Stones to be making “noise” instead of music.

Frankly, I’m of the opinion that art and music deserve space to evolve. Unlike the story of Gilgamesh, these definitions are not etched in stone. And if you think I’m out of line for comparing myself to Claude Monet or Elvis Presley, or for adding a couple metrical feet to my limericks, then you and your high horse can head straight back to Mesopotamia. This is MY kingdom, after all.

Further Reading

If you enjoyed this thought-provoking analysis, please consider purchasing one of my books or subscribing to the blog. You might also want to check out some of these popular articles:

2 Comments

Long Live The King Of Limericks!

Indeed, the King of Limericks and Ruler of Research has spoken!