14 of the Most Famous Limericks: Literary Classics

5 Reasons Isaac Asimov’s dirty limericks are truly awful

The history of the limerick is something of a mystery wrapped in a wisecrack. Trying to determine who wrote the first limerick is a little like asking who told the first the knock-knock joke or who recited the first fairy tale. But whatever we lack in certainty, we can more than make up for with literary license and sprightly speculation.

The artist and children’s author Edward Lear usually takes the credit for having written the first limerick, but the actual history is rather more complicated than that. Some attribute the genre to William Shakespeare, who’s given us more notable quotables than the Holy Bible. Others claim to have traced the limerick as far back as Thomas Aquinas and the medieval troubadours, writing in Latin and French respectively.

In modern times, people tend to think of limericks as the genre of the off-color, the indecent and the absurd. But that has not always been the case. And I’m here to demonstrate that it need not remain the case.

In the following article, we’ll take a closer look at the history of the limerick. We’ll examine where they came from, how they got here, and where they’re headed.

An Ancient Limerick: Thomas Aquinas

Scholars of limerick history are a rare and quixotic breed, but we get the job done. And the general consensus is that Saint Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274), who famously united Aristotelian philosophy with the doctrine of Christianity, wrote the earliest recorded limerick. We can also agree that the limerick has come an awful long way since the 13th century.

Sit vitiorum meorum evacuatio

Concupiscentae et libidinis exterminatio,

Caritatis et patientiae,

Humilitatis et obedientiae,

Omniumque virtutum augmentatio.

My Latin is pretty rusty, but obviously the saint and church scholar was not waxing poetic over a young maiden from Kent or a fine lady from Cork. In fact, we can say with all seriousness that he was writing a limerick about the holy of holies, and that’s no euphemism for any part of the anatomy.

You could also argue that Acquinas’ limerick loses something in translation. This being the standard rendering, I would have to agree.

Let it be for the elimination for my sins,

For the expulsion of the desire and lust,

For the increase of charity and patience,

Humility and obedience,

As well as all virtue.

Limerick as prayer

The verse written by Aquinas employs the AABBA rhyme scheme of the limerick, but it’s difficult to judge the poetic meter. Ultimately, the God-fearing monk was writing more of a prayer or an incantation, rather than anything we would customarily think of as a limerick. And the word-for-word translation doesn’t do Aquinas any favors.

So it’s about time someone translated the saint’s 750-year-old Latin limerick into a proper, modern, English limerick. And here goes:

To circumvent brimstone and fire

Expelling unsav’ry desire

I piously pray

And devoutly obey

As my soul soars progressively higher

Here we see that prayers and limericks are not irreconcilable. But the rhyme and meter of a classic limerick does lend a certain sense of levity to the sacred substance. And in fact, I’ve written hundreds of prayer-like limericks. For example:

There’s no need for ritual, doctrine or fear

Whenever you’re ready the truth will appear

Prepare to receive it

And then you’ll believe it

The prophecy comes like a voice in your ear

So, is the history of limericks coming full circle? From prayer to nursery rhyme to dirty joke and back to prayer? We shall see.

Shakespeare’s Place in the History of Limericks

When you’re looking for the etymological root of an English phrase or expression, your best guess will usually be to trace it back to William Shakespeare. But did the Bard invent the limerick? Probably not.

Typically, Shakespeare wrote his plays and sonnets in flawless, iambic meter (da-DAH-da-DAH-da-DAH). Almost never in his works do we come across the anapestic meter characteristic of limericks (da-da-DAH-da-da-DAH-da-da-DAH). But there is this example of a drinking song from Othello (Act II, scene III), which also uses the AABBA rhyme scheme. So perhaps this is the earliest English ancestor to the modern limerick.

And let me the canakin clink, clink;

And let me the canakin clink

A soldier’s a man;

A life’s but a span;

Why, then, let a soldier drink.

As far as Shakespearean verses go, this is hardly the most memorable. And not hard to see how we’ve overlooked it for all these years. At this point, I’m tempted to think that it was simply inevitable for a writer as prolific as Shakespeare to eventually stumble into something resembling a limerick.

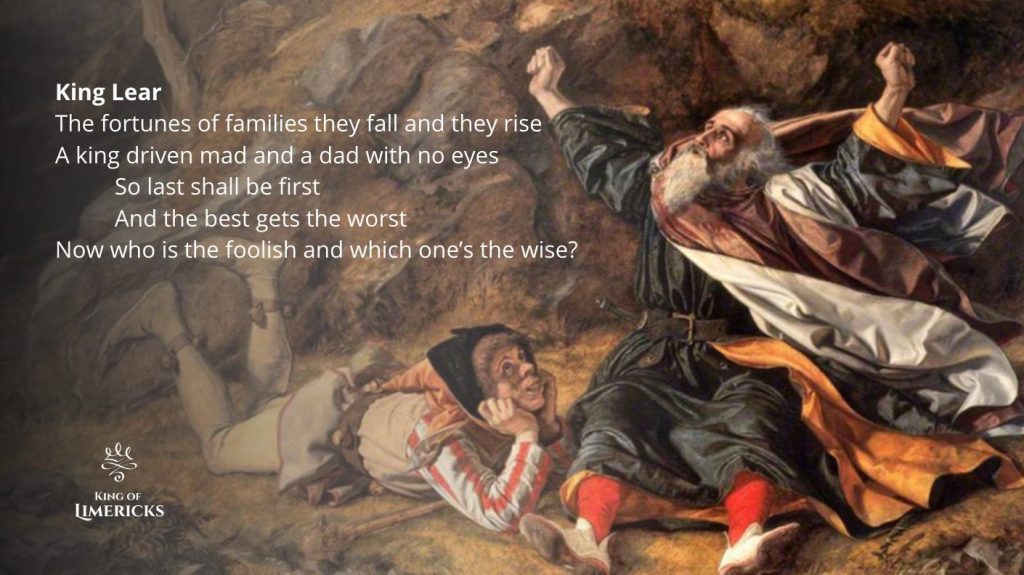

Shakespeare as inspiration for limericks

Whether or not he penned the first limerick, the master playwright holds a secure place in the history of limericks, if only for the inspiration he provides to hack poets like myself. Consider some of the following limericks, from yours truly, based on selected works of Shakespeare.

Hamlet

There’s a poor Prince of Denmark who’s all too aware

The effects of his actions could lead to despair

A man plagued by Will

Was determined to kill

Now show me a life that this hero can spare

A Midsummer Night’s Dream

An Athenian daughter all down on her luck

Partakes of a potion provided by Puck

Lysander meanders

With aimless bystanders

As flowers bring magic to those who can pluck

Twelfth Night

There’s a comedy found in the Folio

But tragic for hapless Malvolio

The unlucky fellow

Comes clad in bright yellow

To mount an unholy imbroglio

The Popularization of Limericks

Without a doubt, the best known name in the history of limericks belongs to the illustrious Edward Lear (1812-1888). The 19th century artist was quite accomplished in his own day, but today Lear is best remembered for The Book of Nonsense, a collection of humorous, family-friendly limericks published in 1846.

As far as poetry goes, this volume leaves a little something to be desired. But among the children of the mid 1800s, the book was a real smash hit. The ridiculous scenes portrayed in his verses don’t always make sense, and he all too often rhymes a word with itself, which I have a hard time with. But his limericks do elicit the occasional chuckle.

The Book of Nonsense is now available in the public domain, so you can peruse the entire anthology and judge for yourself. But for the historical record, it’s worth pointing out that these five-line rhymes were never referred to as “limericks” within Lear’s own lifetime.

Rise of the Saucy Limerick

The first known use of the term “limerick” in reference to a five-line poem rhyming in AABBA appeared in a letter written by Aubrey Beardsley in 1896. And how the pithy poetic form came to have this name, and its ineluctable association with Ireland, remains another historical enigma.

There are a few competing theories, but the best explanation is that W. B. Yeats and other figures in the Irish Literary Revival belatedly applied the name limerick to this genre, some time after Lear’s death in 1888. By doing so, these Irish poets would create an implicit connection with the Maigue Poets of Croom, in the County of Limerick.

And if we can know anything about the Irish race, we can say that they are indubitably clever and irreverent. Around the same time that the term limerick was gaining literary currency, these poetic morsels were also taking on an unequivocal shade of indecency.

You need only take a glance at a handful of the most famous limericks to see that Edward Lear’s family-friendly nursery rhyme format had evolved into something distinctively unsuitable for mixed company.

Like so many things that embark on this race to the bottom, this less-than-epic quest for the lowest common denominator, the limerick has remained condemned to its unsavory circle for more than a century. But must it dwell here for eternity, or is there some hope for redemption?

The Future of Limericks

The social and political upheaval we’re seeing around the world is sending many mixed messages. On the one hand, the rise of populist nationalism and reactionary politics is somewhat disturbing to say the least. On the other, I can read it as a reaction to the incredible social progress we’ve seen over the last 50 years.

Meanwhile, we’ve been witnessing a dramatic rise in religious fundamentalism. Is it because the rapture is finally approaching? It is merely a frightened response to a massive wave of spiritual awakening that’s been going on since the mid 1960s?

Indeed, I’m convinced of the latter and that we’re in the midst of a second Axial Age. Not everyone is going to embrace this radical shift with graceful composure, but I feel like hope is all around us. And as the history of ideas moves forward, the history of limericks can (and should) move with it.

Writing provocative limericks laced with sexual innuendo is a pleasant enough diversion, and far be it from me to suggest we abandon it altogether. But let’s not stop there. Limericks are perfectly adequate for expressing the carnal instincts, but they can also embrace the higher purposes and principles. As you’ll see from this website, I’ve taken inspiration from Nathaniel Hawthorne (Moses from an Old Manse), Joseph Campbell (The Masks of God), and Jack Kornfield (Spirit Rock Meditation Center), just to name a few.

Limericks have the unique capacity to deliver a quick, sharp message, with irony, brevity and wit. But this is irony in its best sense. This is an irony that reveals the ambivalence of human nature, coming to terms with our discarded shadows and our state of interdependence. Finally, limericks allow us to laugh. And what better than laughter to pump oxygen into those dark recesses of the soul?

Further Reading

If you enjoyed reading about the history of limericks, please consider sharing the post or subscribing to the blog. You might also want to check out some of these popular articles:

- Limericks about World Religions

- Limericks about Inner Wisdom

- Penetrating Limericks about Dostoyevsky

- Serious Limericks: There once was an unsmiling rhymer

5 Comments

Does anyone know who holds the world’s record for the most Limericks written in a lifetime?

There’s an author whose skills were terrific

With output supremely prolific

The name of this poet

I sadly don’t know it

The records just aren’t that specific

A lighthouse man down in Nantucket

Got tired and quit he said chuck it

A damsel named Faye

Moved in to stay

With so much stuff they had to truck it

A poet he is esoteric

Calls himself Fred, should Eric

Well-read and well versed

His pen and lips pursed

He’d be right at home as a cleric

Philosophers oh how they think

Some thoughts even drove them to drink

A treatise so deep

Lulled me to sleep

‘Bout knee-deep my eyes start to blink

Sorry, I couldn’t resist. I’d like to talk with you about a couple of things if you have time. Glen Sherwood, an old curmudgeon in Utah.

Hi Fred, I would like to quote this page in an essay I am writing for my University. Could I please have the publication date as I cannot seem to see one.

Many thanks

Emily King

The most wordy author in limerick lore

Wrote dozens per day, and each evening, a score

He compiled them by columns

In numerous volumes

But in bleak anonymity. Fame? Nevermore!