The Dreams of Millie: A children’s story

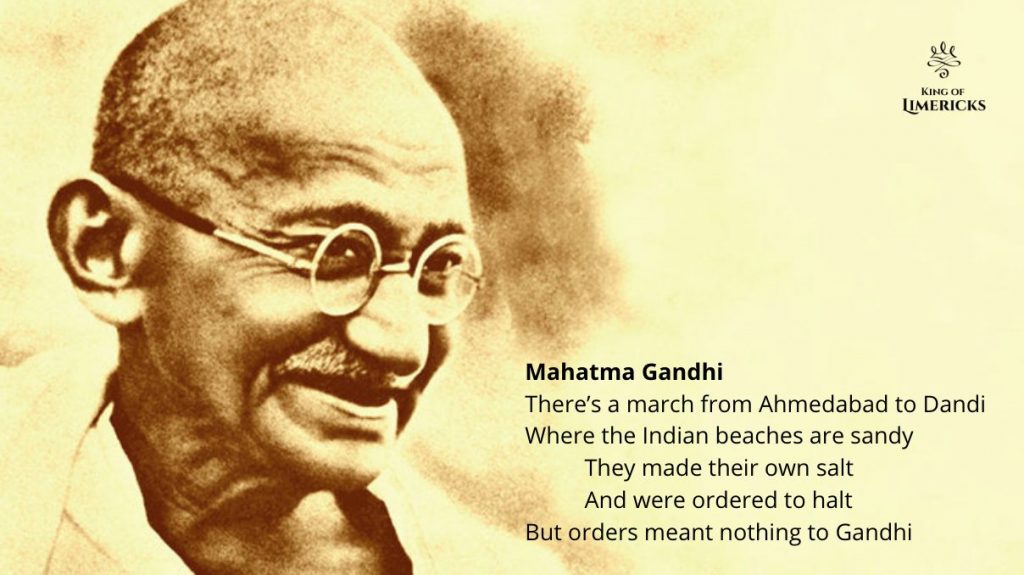

Unforgettable Limericks about History

If you ever see me sitting alone on a park bench, next to a trail, or in the bath tub, scribbling something on a scrap of paper, I’m probably just writing another limerick. It’s a fairly safe assumption. But sometimes I’m writing something with a lot more than five lines, and casual onlookers still assume I’m writing a limerick. So the question is, does a limerick have to have five lines?

By definition, a limerick is a short poem with five lines. The first two lines rhyme with the fifth line, and the third and fourth lines rhyme together. Traditionally, lines one, two and five have nine syllables each, and lines three and four have just six syllables each, more or less. Finally, the meter of the poem is anapestic, which is something like da-da-DAH, da-da-DAH, da-da-DAH. And the poem is often funny or indecent, but not necessarily.

The critical criteria of a limerick

For me, the rhyming of a limerick is pretty simple. Although some clever rhyming can make the poem more interesting and amusing. But the key to producing consistently satisfying limericks is to get the rhythm right. Something about that anapestic meter just makes the poem bounce along merrily, with a twinkle in its eye and a smile on its lips.

After writing a thousand or more limericks about everything from Photosynthesis to Existentialism, I have to say that the anapest rhythm is pretty deeply ingrained in my brain tissue. So when I sit down to write anything, there’s a good chance it will come out sounding like a limerick. And as my kids will tell you, the sentences that come out of my mouth end up up rhyming far more than they need to.

But just because something rhymes and and moves along in anapest meter, that does not make it a limerick. After all, the limerick refers to a very precise and well-defined form of poetry.

On the other hand, I write so many limericks, and I’ve even adopted (with no absence of irony) the title of King of Limericks. So if someone chooses to refer to one of my longer poems as a limerick, it would not be entirely accurate, but I can still accept their use of the term in casual conversation.

It’s like walking into the Monterey Aquarium, setting your eyes on the great menagerie of sea life, and exclaiming, “Wow, look at all those fish!” Now strictly speaking, a lot of those creatures are actually marine mammals and echinoderms. So the use of the word “fish” is not perfectly correct, but we are willing to let it slide.

Now “fish” is more of a general term, like “poetry”, while “limerick” refers to something pretty specific, like an Elizabethan Sonnet, or a bivalved mollusk. So maybe my analogy doesn’t exactly hold water.

The fact is, I much prefer when language is used with precision. So if you refer to a 20- or 30-line poem as a limerick, I might not object out loud. But deep inside, I will surely be experiencing a profound sense of unease.

So please don’t do it.

Longer poems that resemble limericks

The following poem maintains some pretty consistent anapest rhythm, but it contains 16 lines (eight rhyming couplets, as a matter of fact). No one in their right mind would classify this as a limerick, but I can assure you that many of the biggest limerick fans are not in their right minds.

So this is clearly not a limerick, although it does bare certain resemblances. Adding a bit of humor and vulgarity to the poem can make it sound even more like a limerick. I’ve already filled this website with enough limericks about philosophy and spirituality, so I think now would be a good time to share some poetry dealing with matters less refined.

The Putrefacts of Life

Everything beautiful grows out of shit

My daughter was born she was covered with it

But look at her now with her radiant glow

Immaculate skin and her teeth white as snow

In a similar fashion the veggies we eat

Are grown from the soil that’s tempered with shete

What goes IN must come OUT in the cycle of life

But don’t shovel shit with a fork and a knife

To feed yourself well will require some nerve

To kill every bite of the food that you serve

For all that we eat was alive at one time

Except for the salt that was brought from the mine

And once it’s digested we know where it goes

Right back to the field where the vegetable grows

And new sprouts emerge as they’re fed by the sun

You can pee on them too if you’re looking for fun

Maybe that was too tasteless for you to stomach. But trust me, I can do worse. Here’s another example, concerning a similar topic, but treating it with slightly more deference and distinction.

The G.I. Tract

This is the system of human digestion

Together I think we can answer the question

What happens to food when we put inside us?

Open up wide and the passage will guide us

The path of digestion begins in the mouth

On a journey that leads irreversibly south

The teeth do their job, chewing food into pieces

Now enter the enzymes saliva releases

Epiglottis protects you by closing the gap

At the back of the mouth with a soft, tender flap

If you choke on it now you know something went wrong

Then — gulp — the esophagus leads us along

From here to the stomach, just come right this way

Where acids and juices all come into play

It’s here the digestion of proteins takes place

With help from the peptides and gastric lipase

Exit the duodenum and pass by the spleen

To the liver, the organ whose task is to clean

Removing the toxins to make your blood pure

A pivotal process for health, to be sure

We’ve reached the intestine, the one they call small

But at nearly nine meters, it’s not small at all

A segmented tube running this way and that

Absorbing nutrition and processing fat

The larger intestine, it’s known as the colon

Mind what you eat so it doesn’t get swollen

Food high in fiber to work it all through

And arrive at the end with a smooth number two

Finally a five-line limerick

If you made it this far, you definitely deserve a bona fide limerick. This poem is related to the first two in subject matter, but keeps to the traditional five-line format of the limerick. You might notice that the longer lines here have 11 syllables and the shorter ones only have five. If that offends your poetic sensibilities, then I apologize. But I think it sounds alright.

You’ll also find that this limerick is neither humorous nor off-color, common but not essential characteristics of the traditional limerick. I hope this doesn’t come as too much of a disappointment. I have to make some attempt at originality, after all.

Carrion Luggage

The wisdom of vultures, beyond what we think

Consuming nutrition from corpses that stink

Just see how they’re fed

On that which is dead

To prove that the cycle of life is in sync

Further Reading

If you enjoyed this discussion of five-line limericks and anapestic poetry with more than five lines, please consider sharing the post or subscribing to the blog. You might also want to check out some of these popular articles:

- Serious Limericks: There once was an unsmiling rhymer

- The Legend of Rusty the Wagon

- What is a limerick?